EasyCheckout

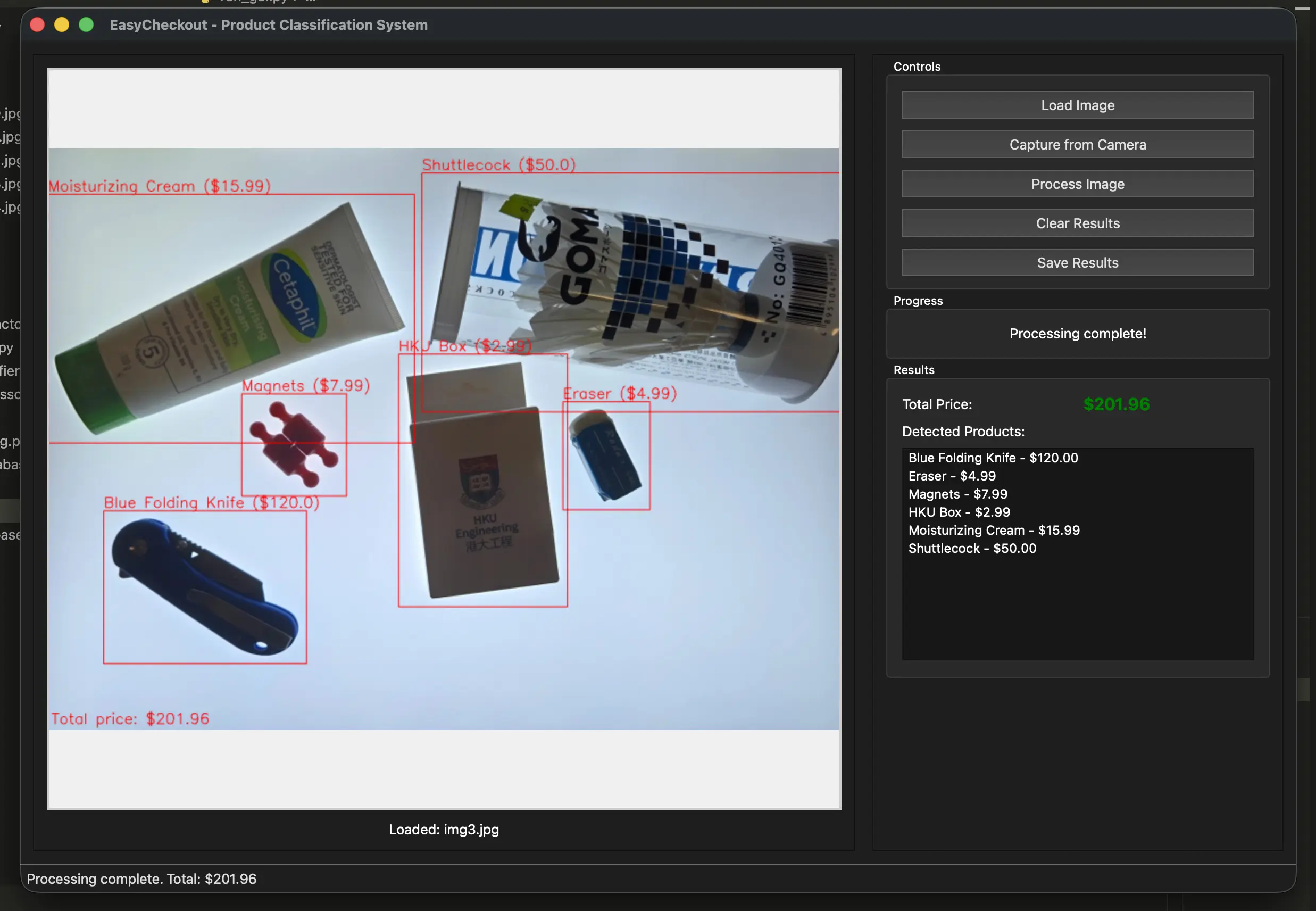

EasyCheckout is my attempt at building an AI project that behaves like a real system instead of a one-off demo. The idea is simple, take a single image of multiple items on a counter, identify each product, and calculate the total price automatically. Under the hood, it’s a pipeline that combines classic computer vision preprocessing with modern deep learning embeddings and vector similarity search, wrapped in a PySide6 GUI so the whole thing is actually usable.

Project Overview

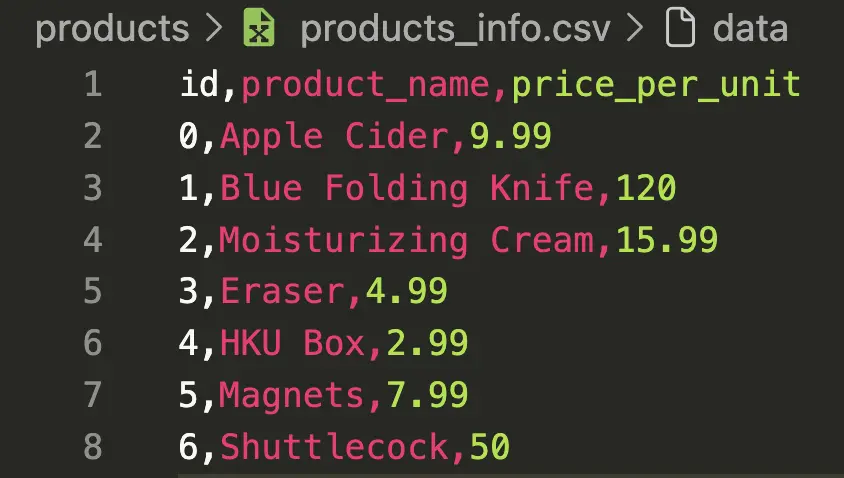

At a high level, EasyCheckout does two jobs. First, it finds individual product regions inside a cluttered scene. Second, it matches each cropped product against a small to medium inventory database and retrieves its metadata, specifically name and price, then sums everything into a cart total. I intentionally avoided training a closed-set classifier because I didn’t want a workflow where adding a new product means retraining a model and hoping accuracy doesn’t collapse. I wanted a system where adding products is closer to “add a reference image and update a CSV.” Which makes it easy to use and manage.

The end result is a modular Python project, a preprocessing module, a Vision Transformer feature extractor, a ChromaDB-backed vector database layer, a matcher that joins embeddings with product metadata, and a GUI that orchestrates the entire flow and visualizes the output. It’s not production-grade checkout automation, but if paired with real world hardware and replace the current GUI with a production one. I will be ready.

Motivation

I built this because I wanted something practical with AI. I’ve done the “model predicts something in a jupyter notebook” type of projects before, and they’re fine for learning, but they don’t teach you what happens when real inputs are messy and every component depends on the previous one not failing. I also didn’t want to build something that already exists in a thousand identical GitHub repos. I wanted a project where the output is obvious to anyone watching, and where the constraints feel like real life, where lighting changes, objects overlap, and the system still needs to return something coherent.

Inspiration

The inspiration came from two places. The first is Uniqlo’s RFID checkout experience. It’s smooth because the identification problem is basically solved, every item carries a tag, and the checkout station just reads it. That’s not “AI recognition,” but the UX is perfect, put items down, get total.

The second is the A1 Bakery checkout systems where a camera looks at a tray and recognizes what’s on it. That idea stuck with me because it’s the opposite approach. Instead of relying on tags, the system tries to understand the image. It’s harder and less reliable, but it’s also much more flexible in scenarios where tagging is unrealistic. A1 Bakery Article

EasyCheckout is me trying to expand the idea of using image recognition for checkout. But with any products you want, not only bread.

System Architecture

The pipeline is deliberately staged because each stage has a different failure mode and I wanted those failures to be debuggable. The process starts with image loading and normalization so the data is in a predictable shape. Then a product detector step segments the scene into individual regions using brightness-based thresholding and contour filtering, producing cropped images for each candidate product. Each crop goes into a feature extractor based on a Vision Transformer backbone, where I remove the classification head and treat the model as an embedding generator. Those embeddings are then queried against a ChromaDB collection that stores embeddings for the reference product images in the inventory. The matcher takes the nearest neighbor results, retrieves the associated product metadata from a CSV, and aggregates everything into a final list of detected items and a total price.

That “embeddings + vector search” choice is the core design decision. It turns the problem into retrieval rather than classification, which is a better fit for “small inventory that changes over time” and for a project where I want the onboarding story to be simple.

Features (What it can do in practice)

In practice, there are two ways to use it. The GUI is the main one. It lets you load an image from disk or capture one from a camera, run the full detection and matching pipeline, and see annotated results with bounding boxes and predicted labels. It also computes the total automatically based on matched items, and it can export the annotated output for record-keeping or debugging. The second way is a CLI batch mode that indexes product images from the products folder, processes a test folder, writes results into an output directory, and prints logs that make it obvious where things go wrong.

Performance-wise, the first run can be slow because model weights need to download and initialization costs are real. After that, it’s responsive enough for a demo. With a GPU, the inference step becomes much less of a bottleneck, but the preprocessing and data movement still matter.

These are both built for demo. The main processing logic is here, the only thing left for production is that it needs a sophisticated inventory system and the physical checkout setup.

Market Analysis (What gap this fills)

I’m not pretending this replaces a POS system. Barcode scanners are cheap and extremely reliable. RFID checkout is even smoother, but it requires tagged inventory and dedicated infrastructure. Human cashiers are flexible and handle edge cases effortlessly, but labor cost and throughput are constraints.

A system like EasyCheckout makes sense in narrower conditions, small or curated inventories, predictable counter setups, and environments where you can control lighting and camera placement. Bakeries are the obvious example because items are placed in consistent ways and RFID tagging pastries is not realistic. Small pop-up stores or internal prototypes are another case, where the main goal is to validate whether visual recognition is even feasible for the product set.

Challenges and Solutions

Separating multiple products from a single scan was the first real blocker. In theory, instance segmentation models should solve this immediately, so that’s where I started. In practice, they were a bad fit for my setup. Most segmentation approaches expect labeled data, and I didn’t have it. The whole point of my system is that I don’t reliably know the “true” product name at capture time, and even when I did have a label, the segmentation quality still wasn’t consistent, especially with transparent packaging where boundaries are ambiguous and the model behaves like it’s guessing.

After that, I went through the usual computer vision toolbox. I tried edge detection-based pipelines, then color-based methods, and a bunch of variations in between. None of them were stable enough for my scenes. Edges break on low-contrast items and reflective surfaces, while color methods collapse when packaging colors are similar or lighting shifts. What finally worked best for my constraints was a brightness-difference approach. I put a light board as the background, then detect “product” regions as the parts that are noticeably darker than the background. From there, I crop those regions and pass them downstream. Transparent products were still annoying because their detected regions can fragment or partially overlap, so I added a simple rule which is to merge overlapping boxes so at least the system doesn’t split one item into several nonsense crops. It’s not elegant, but it’s the most reliable solution I found without labels.

Choosing the vision model was the second major decision. My first attempt was to use standard classification models, and the limitation became obvious quickly, classification assumes fixed classes and it doesn’t naturally map to “identify this exact SKU in my inventory.” My inventory items are specific and sometimes visually similar, and I needed matching, not just category prediction. That’s why I moved to a Vision Transformer feature-extraction approach. The goal wasn’t “predict class,” it was “generate an embedding that can distinguish fine-grained differences,” then retrieve the closest product from the database. After testing different sizes, I settled on DINOv3 Base at around 87.6M parameters, described as a distillation of DINOv3 7B. The practical reason was boring but important, it can run comfortably on CPU hardware, which matters if this is ever going to resemble a real checkout kiosk instead of a GPU-only demo.

Overlapping products is still the problem I haven’t solved. Because my cropping depends on brightness difference, two products that overlap can become a single connected “dark region,” and the system treats them as one item. That breaks everything downstream because one crop can only match to one product embedding, and the pricing becomes wrong immediately. I don’t have a clean fix for this yet. Right now, my system works best when items are placed with minimal overlap, which is a limitation I’m not going to pretend is acceptable for a real checkout scenario.

Conclusion

EasyCheckout is a working prototype that demonstrates an approach I like. In a controlled environment, it produces results that feel like the beginning of a real checkout experience.

Right now, the brightness-based cropping approach is the main reason the system works at all, and also the main reason it can fail badly. In a controlled setup with a light board background, it is simple, fast, and surprisingly reliable. The question is whether I should keep investing in it or replace it entirely. If I can make it handle overlap and transparency more consistently without turning the pipeline into a fragile mess of thresholds, then it’s worth keeping because it’s cheap to run and easy to explain. If overlap remains a hard failure mode, then I should stop patching it and switch to a detection/segmentation approach that is designed for separating touching objects.

The next step is to stop treating this like “an algorithm on my laptop” and build the full kiosk setup. That means locking down the camera position, distance, background, and lighting as part of the system design, not as an afterthought. If the environment is part of the product, then engineering the environment is not cheating—, it’s literally how you make the pipeline stable.

After that, I need to test it in more extreme scenarios on purpose, harsher lighting, shadows, reflective packaging, transparent products, motion blur from quick scans, different camera sensors, and especially overlapping items. If it survives those tests with only small degradations, then the brightness approach is validated. If it collapses, then the conclusion is clear that the segmentation stage needs to be replaced, and the rest of the system should be treated as the reusable part that plugs into a better front end.